Built by Johnson & Johnson in 1926-1927, these buildings are still in use today. They were among the first structures of their kind in their region to have indoor plumbing, electricity and hot water, and they changed the lives of the families who lived in them. What were they? A remarkable collection of homes near Gainesville, Georgia called Chicopee Village.

In 1916, Johnson & Johnson acquired a 93-year-old company called The Chicopee Manufacturing Company – a famous textile mill that originally grew out of the Industrial Revolution and the need to make United States textile manufacturing independent of Britain. Johnson & Johnson was the largest manufacturer of sterile surgical dressings during the Nineteen Teens, and was running its manufacturing lines around the clock in order to make enough dressings to treat wounded soldiers during World War I in Europe — while at the same time meeting the demand for sterile dressings from American hospitals. Johnson & Johnson acquired the Chicopee Manufacturing Company of Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts in order to increase capacity to meet that demand.

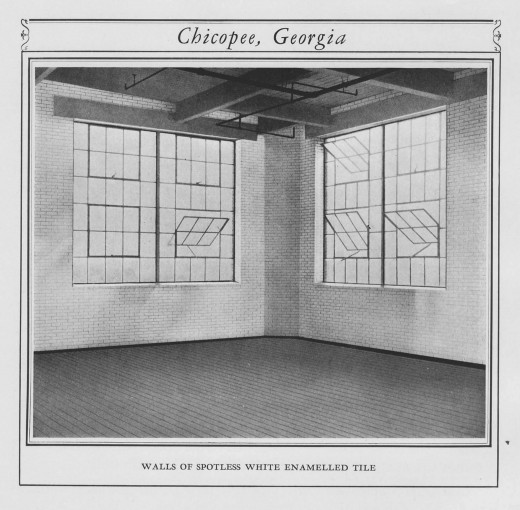

The Chicopee Manufacturing Company was founded in 1823, making it officially the oldest operating company to join the Johnson & Johnson Family of Companies. (Codman & Shurtleff, founded in 1838, was the next oldest.) In the 1920s, Chicopee was expanding, and land was purchased for the building of a modern, one-story plant near Gainesville, Georgia. Most textile mills at that time were rather dark, multi-story Victorian era buildings with few amenities. So of course Johnson & Johnson set out to build the most modern, one-story, light-filled building with all of the latest modern conveniences. The new Chicopee mill in Georgia attracted a lot of attention, since it looked more like a college campus building than a textile plant. It was the nation’s first modern, single-story textile mill, and it changed the way textile mills were constructed.

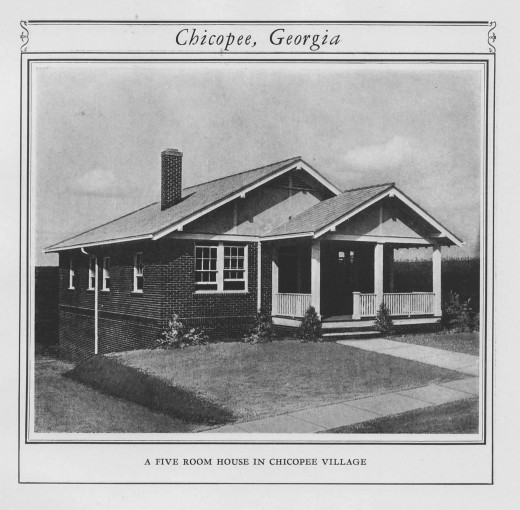

In addition, the Company constructed a village for employees of the new mill – called Chicopee Village. Chicopee Village had 250 modern houses, a school and a medical facility.

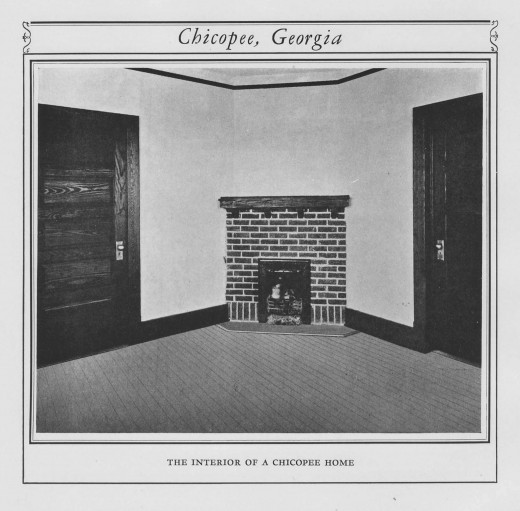

Instead of being designed with identical houses (which would have been easier to build), Chicopee Village contained 31 (yes, 31) variations of modern brick homes. The houses were among the first in Northeastern Georgia to have indoor plumbing, electricity and hot water.

Every house had a modern kitchen and bathroom, screens in the windows (important to keep disease-carrying insects out) and porches. In most cases, water and electricity were supplied to the residents for free. For families with cars, there were grouped garages throughout the community. For those without cars, there were buses into Gainesville. For many of the families who moved in – perhaps coming from a residence without electricity or indoor plumbing — the houses must have seemed nothing short of miraculous. One resident wrote to Johnson & Johnson: “ ‘We had a modern five-room brick house with all of the modern conveniences, and went to work in a modern mill where all was light and clean. A new life was opened for us.” [Letter from Chicopee employee to Johnson & Johnson, as quoted in Robert Wood Johnson, The Gentleman Rebel by Lawrence G. Foster, Lillian Press, 1999, p. 171]

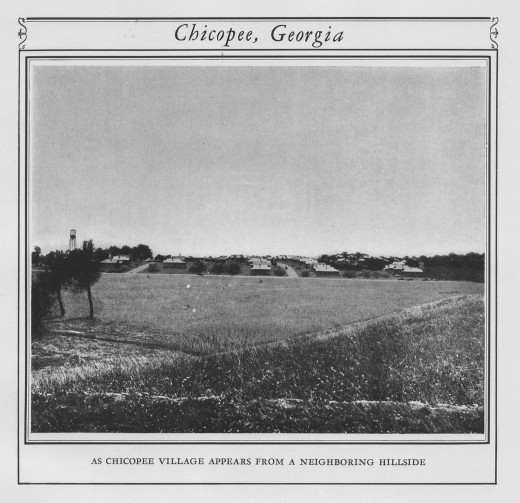

But there’s more. Instead of being laid out in a straight grid, Chicopee Village was designed to have rolling hills and winding roads, to make it more attractive for its residents. And in an era in which many workers’ homes still fronted on unpaved streets, Chicopee Village had paved roads and sidewalks, as well as a sanitary sewer system and storm sewers. There were modern electric streetlights as well as electricity in the homes and, in a progressive and far-seeing move in 1926, all of the electrical wiring was underground – both to improve the view and prevent power outages caused by wires blowing down in storms.

“All village wiring is underground and 10 carloads of material were required to construct the conduits in which these wires are buried. When wires are run underground in this way they cannot be short circuited or blown down by storms. Their concealment, moreover, improves the appearance of all streets and houses while the landscape architects have given every other possible consideration to the symmetry and beauty of this ideal mill community.” [Chicopee Georgia, Chicopee Manufacturing Corporation of Georgia, prepared and published by Doyle, Kitchen & McCormick, Inc., New York. Undated (1920s) hardcover book in Johnson & Johnson archives, p. 16]

The houses in Chicopee Village were in walking distance to Chicopee Mills – an important consideration in an era before everyone had a car. There was also another reason: walking was good exercise, and the Company wanted to promote good health and exercise for the mill employees and their families.

But there’s still more. Chicopee village had a modern school that was designed to be a model for the state of Georgia, and it had a community center. The community center was available for social gatherings such as dancing and movie nights, and it had a gymnasium for exercise and team sports. Behind the community center were a swimming pool, tennis courts and athletic fields for residents. And behind that was a beautifully landscaped park. (By now, readers may be asking themselves “When can I move in?”)

There were also public playgrounds in Chicopee Village, as well as a store for residents that sold fresh vegetables and other foods. (By now, readers would be forgiven for demanding to be able to move in.)

Health, safety and well-being were primary concerns. (A book in our archives about Chicopee in Georgia has chapter headings titled Safety, Health and Happiness.) Not only did the mill have the latest safety standards and equipment (including automatic fire sprinklers), but the village had a telephone relay system for residents to report any kind of emergency. A water filtration plant was built to provide pure, filtered water to the community. Chicopee Village also had a trained nurse in residence.

Johnson & Johnson had some precedent for building employee housing. Just a few decades earlier, the Company bought and renovated houses for employees in New Brunswick, on Morrell Street. Chicopee Village was of special interest to General Robert Wood Johnson, and he put his beliefs about the social responsibilities of business into its planning and construction. With Chicopee Village, Johnson & Johnson put into practice its emphasis on health, safety, hygiene and quality of life for employees (and by extension, their families), and created a model community that’s still talked about today by the descendents of those who lived there.

By the way, if you’re interested in taking a tour through one of the Chicopee Village houses in the present day, you can do so for a short time on this site.

In the textile industry of the 1920s, Chicopee Mills and Chicopee Village were seen as the greatest advance ever taken to upgrade the status of southern textile employees. [Robert Wood Johnson, The Gentleman Rebel, by Lawrence G. Foster, Lillian Press, 1999, p. 171] And although we take things like indoor plumbing, electricity and central heating for granted today, for the employees who were experiencing these necessities for the first time, it was truly life-changing. Years later, Robert Wood Johnson would codify the ideas that influenced the building of Chicopee Mills and Chicopee Village in Georgia into a one-page document that still guides Johnson & Johnson today: Our Credo.